Reading prompts for the class of November 8 (by Professor Diana V. Almeida)

Comment on one or more prompts (on "fish(y)" poems by Moore, Bishop, Oliver, Harjo, and Limón)

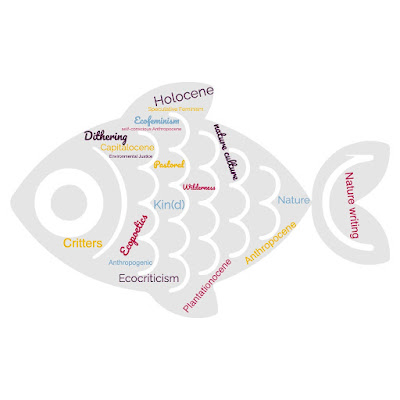

(illustration by a student of Ms. Caitlyn Trimble, that your teacher found in the infamous platform X: https://x.com/MsTrimbleEng/status/991844239607648256/photo/4)Do you fish?

Do you keep / cook and eat / talk to fish?

What do you know about (old and contemporary) fish?

How do these fish swim around from one text to the other?

Could the relationship to these fish be determined by the authors’ gender?

Can you think about a music and a work of visual art relating to fish / the ocean /

water? How do they help you to read these texts?

Answer to the 4th question, stating how the figure of the fish appears at each poem, showing the circulation and evolution of this fish thought the sequence of poems.

ReplyDelete1. Moore: Here we have description (if not the most beautiful and poetic one can imagine) of the otherworldly place the fish inhabits and how it does so.

2. Bishop: After observing the fish and its environment, pum, you caught it. But in this catch the beauty and detailed sublimity of the fish strikes you, as it embodies and reflects that other universe where it leaves and that now you hold on your hand, with your instrument/hook. You realized it has tried to be fished before, and always let go, and you do so: you let it go.

3. Oliver: But the same way that before it was not the first time the fish was fished, it happens again and this time the fish is kept, and it dies in the rainbow that once was the reason it was left alive. However, the fish is honored and treated respectfully as a part of a shared life: it is eaten but the eater opens of it to inhabit its spirit. The pain is transmitted and forgiven, from the the killed to the killer.

4. Harjo: The fish that was, which we hunt now, hunts us too with the omen of our transformation in it, hinting both our loss of respect with it and its environment. We are sliding towards an already dead future.

5. Limón. Even more so, we culturally show off this macabre killing spree of our earth mates and call it bravery. The earth/lake does not accept more apologies, and this last poem could be an example of how some resort to poetry as a public and personal wailing wall.

Concerning the 5th question, there are to songs that popped up in my mind. The first one is the self-exploring song by Haley Heynderickx "Fish Eyes", which also deals with the themes of facing the problem (in this case of fishing and its duality of survival and killing) and how we are reflected in the hanging body of the fish. Secondly, I was listening the the Devendra Banhart song "Sea Horse", which outburst in its second half shouting the verse "I don't wanna be born again if it's in this world again".

(1/2) In his book Catching the Big Fish, David Lynch metaforizes the criative process in the following way: "ideas are like fish. If you want to catch little fish, you can stay in the shallow water. But if you want to catch the big fish, you've got to go deeper". The ocean, thus, is a consciousness. It is the act of conscious waiting, of working inwards, that gives the ability to "receive" the fish, as an idea that comes. However, the most important is not to lose track of that idea you caught, and to work your way through it. If the fish is an idea, then the consciousness of the “I” is embedded with the ocean from which he extracts the beginning of the criative process.

ReplyDeleteIn Marianne Moore’s poem “Fish”, there is a self-conscious presence in the own consctruction of the poem, which regards the simple description of a fish in the waves he inhabits. There is a constant interplay between notions of inside and outside, of movement and fixidity; the movement of the words and of form that requires an “outside”, an other, in order for its “inate” qualities to perform themselves. In fact, the poem’s title, “Fish”, lingers onto the body of the poem, it’s part of its movement. It is fixed, yet it is not. The poem, which in its form and distribution between very short, short and long lines, and that in their turn become shorter once again, has the shape and function of a wave.

This idea of simultaneousness of something fixed and moving can be seen in the image “the barnacles which encrust the side of the wave”, as if the wave was a rock and the barnacles in movement, and that gives as well the idea of interpenetration of this two states. In the elements of the naturalistic description in the poem, the idea of the criative act as simultaneous to reading and to criation itself, gives clues to the fish being not only the poem but the making of it, in its natural relation between fish and ocean, waves and ink (“Whereupon the stars, / pink / rice-grains, ink- / bespotted jelly fish”). The defining line, however, is this one: “All / external / marks of abuse are present on this / defiant edifice”, where the “external marks of abuse” point to these strange non-naturalistic elements that are, even so, invocations of naturalism while being naturalistic by the nature of poetry; these marks are present, inside the construction of the poem, in its rhytmn and images; but it is that construction that, at the same time, defies those external marks.

In Elizabeth Bishop’s poem “The Fish” there is also a doubleness regarding the fish and the criative act (and the definite form of the poem). “My hook”, in the first strophe, involves a personal intervention of the “I” in the natural element of the fish the water. While holding the fish by that fishing line, it said the fish is “battered and venerable”. This image seems to evoke her own negation through poetry, of her woman condition. The fish, the doing of the poem and the poem itself, serves as a projection and an idea of poetry, poetry where she is empowered. She catches the fish.

Moreover, she says: “I looked into his eyes / which were far larger than mine / but shallower, and yellowed”, as if the fish’s liver were failing, which can be a reference to her own alcoolism. But, his eyes, do not correspond hers: “They shifted a little, but not / to return my stare”. On the contrary, they diverge towards the light, the outside, and to death. If the poem constitutes a victory (“I stared and I stared / and victory filled up / the little rented boat”), it also constitutes a defeat: the own light in which she sees poetry, as a self-contained but with invasive elements in its constitution, herself, there is also a lack of recognition in her poems: the looks to recognize herself in the poem, as when she tries for the fish to look back, but in the poem she finds the idea of death, of staleness in which she is the movement, but na ironic one.

This is André Osório, I was not logged in apparently when I posted this first part of the commentary

Delete(2/2) There is, as well, a consciousness of the technicity of the fish (“The mechanism of the fish”) through his mouth, the place in the body that is being held by the “I’s” hook, and a consciousness of the “I” in regarding the fish lines she finds already inside the fish as influences, that gave life as well to the poem (at the same time endangering it), namely the poem “Fish” by Marianne Moore, another “outside” in the “inside” of the poem that caughts and releases its aim the act of losing. In this way, the ending is double: “And I let the fish go” means at the same time releasing the fish to its source, the water, at the same time as it invokes the title of the poem “The Fish” (“And I let the fish go”), which i salso a release to its source, but that of the poem’s, another way of making the title contiguous to the inner working of the poetic work. That returning magnifies the solitude of being alone with its conquering, staying outside watching in, on one hand, and reliving inside the repetition of her own exclusion embedded with this frail victory, on the other.

ReplyDeleteQ: How do these fish swim around from one text to the other?

ReplyDeleteThe waves are present in all these texts. They are in the form of the poem as in Moore's poem or Limóns poem, the fish are swimming in this watery, ever moving and changing environment. The waves are also represented in the metre, especially in Bishop's poem.

In the first poem (Moore’s) the title is part of the poem – describing this alien underwater landscape that is home to the fish. The fish are wading, like people, through the black jade. Next in Bishop's a fish has been caught, “the fish” like the title suggests, half out of the water. Not fighting, and we get a poetic description of the fish who has been caught before. The swimming around feels now more like an inspection of the fish itself – and the reminder that it has had to endure this before. And Bishop or the I in the poem tries to relate to the fish, its face and eyes. At last the fish is released in the oil infested water, shining like a rainbow, which is deadly to the fish.

Now in Olivers’s poem, the fish is out of the water, suffocates, and is eaten – straight out – but still his skin is like the rainbow, there is something mysterious about it. And that mystery is transformational, it seems to be a certain adaptiveness, being still able to swim around in the stomach of the poet.

Harjo's poem describes an evolutionary element, that people once were fish, and there some fish in this poem do not swim anymore, they start to walk. But we see the fish swim around in time and thus making an evolutionary connection to people who cannot swim, who will sink, even in their Chevys.

And in Limón’s poem the fish swims in the lake, is taken by the rod to the cooler and then buried by the rose bush. The poet connects the fish to the lake, to the ecosystem, but feels that there is a certain line that is crossed – by taking a swimming fish out of the water and looking it in the eyes and later burying it.

All these poems look at different scenarios, always reminding us of this strong connection between the fish and the sea, because we have to be reminded somehow that fish do swim.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

DeleteQ: How do these fish swim around from one text to the other?

ReplyDeleteI would like to start my analysis by quoting Morton’s famous assertation: “The ecological crisis makes us aware of how interdependent everything is.” In the poem “The Fish” by Marianne Moore, the fish are not so much individuals as components of a larger and more eternal system of nature. Moore depicts the sea in what almost looks like a geological history book using her images of ‘crow-blue mussel shells’, ‘barnacles’ and ‘iron edge.’ Moore’s fish, on the other, are almost secondary characters, lost in the larger portions of rocks and cracks. Here, it is similar to how Timothy Morton describes nature as a “mesh”—where single components could not be untangled from the whole. In this way, Moore’s fish also become included in this complex structure, in this ‘edifice’, which is complex through the historical processes of accumulation and erosion. Rather than drawing attention to the fish and its distinguishing features, Moore provides details relating to the sea and its inhabitants and how those features have remained after years of evolution and survival.

“The Fish” by Elizabeth Bishop presents a departure from this broad ecocritical context to how the speaker interacts with the fish intensely. A close inspection of the fish by the speaker such as its ‘brown skin’, ‘barnacles’, or ‘the five huge hooks’ grown into its mouth—reveals the fish’s personal history. In contrast to Moore’s broad and geological standpoint, Bishop’s poem even evinces a certain degree of empathy for the fish, recognizing its effort to survive as an act of defiance. The act of freeing the fish at the conclusion of the poem is significant in that it acknowledges the fish as sentient beings, rather than merely a source of sustenance. This recognition challenges the notion that the lives of fish are less valuable than those of humans.

In “The Fish,” Mary Oliver develops a link by establishing a parallel between the fish and the self. The speaker metaphorically consumes the fish, and the stylised juxtaposition of words “the sea…in me” indicates their intimate connection and suggests a sensitive ecological relationship. In other words, the act of consuming the fish serves to illustrate the concept of ‘ecological embeddedness’ whereby human beings are a part of nature, rather than as external entities detached from it. This implies that rather than merely observing, catching, or releasing the fish as an “other,” the fish becomes part of the self. This dissolution of boundaries between human and nature is important, for the speaker is both “the fish” and also part of the “mystery” where there are other lives connected.

“Invisible Fish” by Joy Harjo introduces a new dimension by moving away from material representation of the landscape to instead portraying fish as a metaphor for memories of the land. The fish are described as “invisible”: they do not physically inhabit the land but rather occupy a liminal space above it, evoking memories and associations. The fish serve as ghostly reminders of native environment degradation, a warning for the consequences of destruction that humanity brings to nature and native territories. In this regard, Harjo’s poem also prompts the audience to recognize that there is an aspect of nature which can be observed and which cannot, reminiscent of the ‘ghost ocean’ that once supported life but has since been despoiled.

Finally, in Ada Limón's “The First Fish”, the speaker’s ambivalence towards “the terrible mouth” and “the gold-ringed eye” of the fish reflects the moral complexities and the paradox of human interaction with the natural world. Neither does the fish forgive her, but only reminds of her decisions and how sometimes one can be cruel without any intentions. While Limón’s speaker kills a fish, she also bears the responsibility for its death. The phrase “generations of plunder and vanish” is particularly effective in conveying the concept of ‘ecological debt’, which postulates that every subsequent generation is held accountable for and inherits the ecological costs of the preceding generations.

DeleteBy bringing together these poems, these poems offer a multifaceted reflection of the fish as an image representing ecological connectivity, resilience, and responsibility. Notably, there is an inversion in this geographical from Moore’s geological textures to Limón’s moral reckoning, as each poet emphasizes a different aspect of human’s relationship with nature. In this sense, these fish also ‘swim’ through the poems as memories, bridge-makers and as the reminders of the greater picture where we all belong within, a fragile web of life outside but inside each of us that is deep yet delicate. Also, they evoke the very essence of the ocean; its expanse and depth, and how it cradles countless life-forms and memories, histories that rise to the surface only to obscure, sometimes surfacing just long enough to remind us of all we don’t fully know but somehow belong to.

I would like to focus on Moore’s and Bishop’s poems. Each approaches the subject with unique structures and perspectives, giving us different windows into what fish — and water/ocean — symbolize across different narratives and styles. Marianne Moore, for instance, uses a complex, unconventional structure in her poem The Fish, which is filled with enjambments and scientific language. She’s not just describing a fish but building a layered, fragmented scene with colors and textures that create a vivid underwater world, where every creature, from fish to coral, has its own role and agency within the ecosystem. This layered approach makes me think of Radiohead's "Weird Fishes/Arpeggi," https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TNRCvG9YtYI where the constant, rippling arpeggios mimic waves and the ocean's depth. Like Moore's portrayal of marine life as an interconnected web shaped by natural forces and human impact, Radiohead's song feels like an arpeggiated journey through the depths of (sub)consciousness.

ReplyDeleteElizabeth Bishop’s The Fish takes a different route. Here, Bishop catches an old fish and studies it closely, marveling at the evidence of its survival: its “sullen face,” its skin like “ancient wallpaper,” and its mouth full of “five big hooks,” scars from past encounters with humans. It’s a fish that has faced and endured so much, and Bishop’s moment of realization leads her to let it go, shifting from a feeling of dominion to one of empathy. This theme of survival echoes in Radiohead’s line, “Everybody leaves if they get the chance.” Both the fish in Bishop’s poem and the speaker in "Weird Fishes" are survivors, bearing the scars of their encounters but still pushing forward.

These perspectives on survival and resilience change the way I hear the song. When I first listened to "Weird Fishes," I thought it had a dark, almost fatalistic tone, maybe even bordering on something as heavy as suicidal thoughts. But these poems add another layer — one less about despair and more about survival, and even liberation. It’s like surviving a toxic relationship or breaking free from some restrictive life pattern, where hitting "the bottom" leads to freedom rather than an end. Even if there’s an undertone of death (like being "eaten by worms," reminding me of Poe’s The Conqueror Worm), it feels less morbid. There’s a sense of dissolving into something larger - maybe the ocean as a symbol for the subconscious - a place to free oneself from societal pressures, expectations, and rigid structures in order to discover your true self.

The idea of "Weird Fishes" takes on new significance, too. To find your true self, sometimes you have to become strange or “weird” — alienate yourself from what’s familiar, maybe even from parts of your identity, and go through the pain of hitting rock bottom. Only then can you reach that freedom Moore, Bishop, and Radiohead are all circling around in their own way: a freedom that’s tied to letting go, to surviving with scars, and to being okay with the oddness and isolation of ourselves.

I have written this as a response to the last question. But instead of using the artwork as a mediator into reading the texts, I used the texts to interpret the art as a natural result of my changed perspective to the song after reading the poems and listening to it after all these years. I hope it's okay.

Delete“Could the relationship to these fish be determined by the author’s gender?”

ReplyDeleteAlthough the author’s gender does not determine the relationship with the fish, the poems reflect a conscious effort to challenge the gender stereotype of women being more easily sympathetic to animals.

Framed by the debate over hunting and vegetarianism, Plumwood (2004) regards this topic, mentioning the consideration of women as “gentle, passive and peaceful (...) is culturally invariant and incapable of hunting or killing animals” (51). Commonly, hunting is recognized as a gendered activity that displays aggression, unkindness, or a lack of empathy toward other beings.

Elizabeth Bishop, Mary Oliver, and Ada Limón’s poems explore the relationship between fish and the poetic voice, transitioning from passive meditation to the active decision of killing. The three poems begin with the action of catching the fish (“I caught a tremendous fish”, “The first fish / I ever caught”, and “When I pulled that great fish out of Lake Skinner’s”), but distinctively consider the positions and roles of human and non-human.

Elizabeth Bishop’s poem “The Fish” consists of a descriptive narration of capturing, contemplating, and releasing the fish. The uncomplicated catch (“He didn’t fight. / He hadn’t fought at all.”) is followed by a characterization of the fish as unhealthy and homely (“He was speckled with barnacles, / fine rosettes of lime, / and infested / with tiny white sea-lice”), nevertheless the admiration for the animal is abruptly interrupted by the perception of fishing lines still attached to it (“grim, wet, and weaponlike, / hung five old pieces of fish-line, / (...) Like medals with their ribbons / frayed and wavering, / a five-haired beard of wisdom / trailing from his aching jaw”). The negative description of the fish parallels human violence, contamination, and pollution of the sea (“where oil had spread a rainbow / (...) until everything / was rainbow, rainbow, rainbow!”), culminating at the end of the poem with its release.

Mary Oliver’s poem with the same title presents the relationship between fish and the lyric ‘I’ as a reflection of the dualism of human/non-human, that is, the fish exists only as a food resource for the superior human (Plumwood:2004, 44). Therefore, the relationship is only possible when the animal is consumed (“I opened his body and separated / the flesh from the bones / and ate him. Now the sea / is in me: I am the fish”). However, the consecutive lines demonstrate the critique of this perception of human and non-human relations, reflecting that the continuous enforcement of human superiority and natural inferiority will ultimately lead to the submersion of all species (“we are / risen, tangled together, certain to fall / back to the sea”).

Lastly, Ada Limón’s poem visibly challenges the idea of women as incapable of killing animals. Whereas in the previous poems, the fish is either described with compassion and ultimately released or viewed as simultaneously the instrument of food and connection to the sea, in Limón’s poem the fish is immediately referred to as “the tugging beast”. This choice introduces the speaker’s decision to kill (similar to the hunting activity mentioned earlier), differing from the early depictions of the relationship between the fish and the poetic voice. Aware of the common perception of hunting as a gendered stereotype, and therefore that women should be more connected to and sympathetic with nature, the speaker defiantly questions: “Is this where I am supposed to apologize? / Not / only to the fish, but to the whole lake, land, not only for me / but for the generations of plunder and vanish”. Additionally, the poem also includes the fish’s poem of view, signaling the unforgiveness of nature towards the humans' actions (“That gold-ringed / eye did not pardon me, no absolution, no reprieve. / I wanted to catch something; it wanted to live.”). Despite the action of killing, in the last lines of the poem, the speaker not only identifies the fish as its twin but also returns to the idea of hunting as an activity suppressed of “soft emotions” (Plumwood:2004, 51), “the year I killed a thing because / I was told to, the year I met my twin and buried / him without weeping so I could be called brave”.

Delete