Welcome to this course (Topics on North-American Studies: Ecopoetics of Alterity / Forms of Environmental Justice

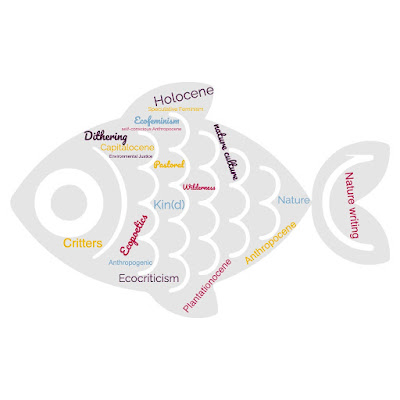

We will study ecology, poetics, others, and kin(d), and more... For now, as you read Donna Haraway's "Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin" (2015), start researching, and (dis)entangling some concepts!

Also, take 13 min to watch this video . The first writing prompt, as this is a processual course, is for you to dare share some of your notes (marginalia to Haraway's text or/and your impressions on the video), using the comment box, in order to kickstart a class discussion.

Forming this comment feels both overwhelming and exciting, as there are almost too many important points to cover in considering Haraway’s concepts of "Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin", and Spahr’s ‘four’ in "Gentle Now, Don’t Add To Heartache", in relation to another work that came to my mind while reading these texts: Yoldaş’s exhibition "An Ecosystem of Excess" (please see the link and video for reference: https://pinaryoldas.info/Ecosystem-of-Excess-2014). Haraway’s article is of great importance not only because it introduces “a myriad of” new concepts (at least new to me) regarding the temporal and spatial terms of Earth, but also because it carries an almost hopeful tone. This hopeful tone emerges through her call for solidarity (and, of course, through the use of adverbs of probability, which implies that there is still a glimmer of light not-so-at-the-end-of-the-tunnel).

ReplyDeleteYoldaş’s work is speculative and quite provocative. It can be described as an artistic exploration of life in the Anthropocene, embodying a form of "plastic symbiosis"—particularly in relation to environmental degradation caused by human activities (especially plastic pollution in the oceans; so, I believe this work could be considered alongside our further readings as well.). In this exhibition, Yoldaş imagines a speculative future in which life adapts to the polluted environment, with new organisms evolving to not only survive but also thrive in an ecosystem filled with plastic. These speculative life forms might, for example, metabolize plastic or incorporate it into their bodies, representing an evolution in response to human excess. Although I do not believe this is what Haraway intended when discussing non-human entities since among what she refers to as non-human there is no plastics, Yoldaş’s vision still connects to the notion of the Chthulucene. In this speculative world, both human and non-human species must find ways to survive together in the face of ecological crises. What I find just as fascinating as these ideas are the names Yoldaş gives to her creations! The speculation feels more realistic upon reading the names of the artworks, which resemble scientific specimens, complete with Latin names and explanations like "Stomaximus: A Digestive Organ for the Plastivore." ...

...

DeleteYoldaş’s exhibition aligns well with some of the terms Haraway discusses, such as the speculative, Capitalocene, biopolitics, assemblages, and, needless to say, the Anthropocene (though not so much with the concept of compost). The exhibition reveals the consequences of the commodification of nature, where land, oceans, and ecosystems are treated as resources to exploit for profit. Plastic waste is a byproduct of consumerism and industrial production, and Yoldaş’s work demonstrates how this waste becomes part of the ecological landscape. It reflects "the heartache" Spahr mentions, though it feels less like an 'ache' and more like a resigned 'what’s done is done, and here is what we get.' "Soda cans, cigarette butts, pink tampon applicators, six pack of beer connectors and various other pieces of plastic" did travel through the stream (which, in this case, is our bodies), and "chloride, magnesium, sulfate, manganese, iron, nitrite/nitrate, aluminum, suspended solids, zinc, phosphorus, fertilizers, animal wastes, oil, grease, dioxins, heavy metals and lead" did go through our skin and into our tissues. However, to me, the feeling in Yoldaş’s work is not one of mourning or lament. Instead, we are simply observing the outcome as it is. Yet, given that the first sentence on Yoldaş’s webpage about the exhibition: “This project starts in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch,” there may still be a tone similar to Spahr’s, who was “born at the beginning of these things.” Yet if there is any ecological grief in Yoldaş’s work, it comes with a sense of irony, as she imagines life forms that adapt and even thrive in the very environments we perceive as toxic and destroyed.

Overall, the exhibition touches on posthumanist ideas as opposed to Haraway’s "compos-ist" one. It challenges the boundaries between living and non-living (not just non-human). Yoldaş’s organisms are hybrids, blurring the lines between biology and technology, between natural and human-made materials. This hybridization evokes an uncanny feeling, along with a calm yet active call for action, considering it responds to the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. However, much like Haraway’s Chthulucene, where human and non-human species are deeply entangled in each other’s survival, Yoldaş’s work also carries a sense of hope. Despite being a different kind of hope, her creatures suggest that life in a posthuman world will adjust to human-made materials, indicating that even if human civilization collapses, life will continue in unexpected ways.

After watching the video “Jane Hirshfield: Contemporary Practices Ecopoetics”, I could not help but compare the story of Gilgamesh to Donna Haraway’s “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin”. According to Jane Hirshfield, Gilgamesh’s wish to become immortal, and therefore, his building of a wall to separate himself, or his species, from the rest of nature represents one of the original sins in the epic. This separation can be compared to the Anthropocene.

ReplyDeleteTo begin with, the Anthropocene is:

“…, [the] unofficial interval of geologic time making up the third worldwide division of the Quaternary Period (2.6 million years ago to the present), characterized as the time in which the collective activities of human beings (Homo sapiens) began to substantially alter Earth’s surface, atmosphere, oceans, and systems of nutrient cycling.” (Rafferty) [(here](https://www.britannica.com/science/Anthropocene-Epoch)).

This is to say that the collective activities function here as establishing a great difference between species, *homo sapiens*, and the others. What establishes this individuation is man’s domination/ manipulation of nature: natural resources, animals, landscapes, agriculture, etc. We can then easily compare the story of Gilgamesh to the Bible and the original sin that *generated* humans. Eli Baggott’s [article](https://www.rolemodelchangemakers.com/home/2021/3/10/gilgamesh-and-genesis-the-same-story-written-twice) for “Role Model Change Makers”, dives into the differences and similarities between the religious book and the epic.

“The concept of original sin as the foundation of humanity is of course apparent in Genesis but is also a central theme in Gilgamesh. In Gilgamesh, Enkidu engaging in sexual interco[u]rse with Shamhat is what makes him a human, capable of an understanding beyond that of a wild animal.” (Baggott).

Besides obvious differences in the plot, both stories depict humans as having been generated by sin. One is then able to conclude that humans’ sinful individuality is what separates them from the other species. Donna Haraway’s article for the *Environmental Humanities* 6th volume reflects on the impacts that the Anthropocene has had on nature. According to Haraway, humans have *overused* (for lack of a better term), the earth’s resources.

“[…] cheapening nature cannot work much longer to sustain extraction and production in and of the contemporary world because most of the reserves of the earth have been drained, burned, depleted, poisoned, exterminated, and otherwise exhausted” (Haraway 160).

Recalling Hirshfield’s mention of the construction of the wall by Gilgamesh one can define it as the epic analogy for the Anthropocene - this dominance/ overtaking by humans. Besides presenting the problem, Haraway proposes a solution that will somehow “save” humanity from destroying itself.

“I think our job is to make the Anthropocene as short/ thin as possible and to cultivate with each other on every way imaginable epochs to come that can replenish refuge” (Haraway 160).

To sum up, cooperation between species is what will shorten the Anthropocene, and consequently, stop the destruction of the earth. Ideally, Homo sapiens is integrated into a system (requiring cooperation), but this anti-social nature, or, to use Haraway’s words, arrogance (p.159), is what will eventually destroy us, as well as all others.

My own comments to the video shared by the professor, and Donna Haraway’s **“Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin"** (2015).

ReplyDeleteEcos: household, poesis: making. Ecopoetics as a sort of awareness of inhabitance. Understanding the present through the past - Gilgamesh. The episode of the making of a wall so that it separated human from the others - an accurate description of the period of the Anthropocene. Hirshfield suggests that it can be through art that we can destroy walls, and “make kin”, with the species with whom we share household. Jane Hirshfield seems to point towards a un-humanizing of our points of view, our perspectives of the world that surrounds us, stepping away from this audacious way of thinking that has taught us that other beings are inferior to humans, and that nature is something to be controlled or manipulated. A period in time that moves away from the Anthropocene - which is a term used by some to describe the most recent period in the history of Planet Earth, meaning that it does not have a proper beginning, but it is considered to have begun in the late 18th century, when human activities began to globally impact the climate of the planet and the functioning of its ecossystems. Thus, it is a new geological epoch molded by humanity and that it is still going.

As Mary Oliver recognizes in her book “Upstream” (2016: p.11): “*Butterflies don’t write books, neither do lilies or violets. Which doesn’t mean they don’t know, in their own way, what they are. That they don’t know they are alive - that they don’t* feel*, that action upon which all consciousness sits, lightly or heavily. Humility is the prize of the leaf-world. Vainglory is the bane of us, the humans.”* I might even add that these butterflies and lilies and violets know and understand the natural world in their own ways, in no way inferior to our understandings. Hirshfield defends a way of not looking from a human ego point of view of the world, and how this perspective may change human existence in itself.

We make take away from Haraway’s text that the author maintains herself as a compost-ist, not a posthumanist. I thought that perhaps this is some sort of metaphor for all that which will be, a sort of poetics of an end (meaning that in the end we are all compost)?

Haraway points toward a type of multispecies ecojustice. A “mammalian job” means to become-earth, become-with other beings, a type of matter-realist worldview where, as Haraway puts it, we make kin, not just through physical chthonic (Earth) means, but through poetics (Hirshfield’s view). Making kin in other ways other than literally giving birth to more babies. Haraway seems, this way, to support a making kin with humanity as it is, as it exists, making kin with what we already have. Although, as is worth mentioning, not in a coercive way, as birthing rights may come into question. Haraway speaks about a “non-natalist” sort of “kinnovation” approach in the world, which may seem like a radical point of thinking.

Thus, Haraway calls for a time that she names the “Chthulucene”, meaning a time of “intense commitment and collaborative work and play with other terrans, flourishing for rich multispecies assemblages that include people”, it is a time that includes the “more-than-human, other-than-human, inhuman, and human-as-humus.”

The current ecological challenge is more than just a problem that requires techno-scientific interventions. It is weighted on the need to reevaluate the position of man in the ecosystem. Jane Hirshfield in her speech, and Donna Haraway, in her essay “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin,” provide complementary visions for addressing this crisis. In furtherance to this, the authors suggest that the way in which the present and the countless other species to come will exist is deeply dependent on the alterations in the modes of thoughts, speech, and existence in relation to the environment.

ReplyDeleteBy tracing the history of human interaction with the environment through literature, Hirshfield talks about the intrinsically human ability and urge to create, to speak and, more importantly, to imbed and portray our experience in words and language. Through literature as a vessel of life, she examines the timeline of how humans have interacted with the surroundings and stresses the fact that many of those stories turned out to be anthropocentric which puts the human race on top of every other form of life on the planet. For instance, in 'The Epic of Gilgamesh', which narrates the ruler’s most dangerous adventure in his pursuit of immortal glory reveals how the king is forced to cut a hallowed tree down. This act begs the question of whether the tree bodily denotes a tree with significance lost to humanity and how far humanity has sought to control nature. According to Hirshfield, such a narrative is the first example of what she calls environmental original sin – a way of thinking that existed long ago and still, influences how people engage with nature.

It is noteworthy, however, that Hirshfield devoted much of her speech to other less well-known literary customs which dream of a better correlation between mankind as well as nature. Among them for example, is the work of a Roman poet called Virgil who wrote ‘Georgics’ with a section on how to take care of specific land, or more recently, the Romantics, more specifically, Keats in whom poems such ‘To Autumn’ show a remarkable intimacy with nature. Nature is never seen as an enemy to be defeated or a reified resource to be plundered, rather, it is understood as a player in the human game which needs to be respected and taken care of. Given Hirshfield’s focus on the power of poetry, it appears that she believes that the modifications in our attitudes toward discussions or even thoughts about nature can assist in building novel and improved systems of existence in the world.

This approach runs parallel to much of the work that Donna Haraway has done but also redirects the discussion to include non-discursive and political issues concerning the ecology. Haraway questions the appropriateness of the term Anthropocene for the present geological era, which has been defined in terms of the impact of people on the planet due to its underlying assumption that sees humanity as a unitary productive force. The issue, from her perspective, is not only ‘humans’ in general but also particular relationships of domination and exploitation, especially those that capitalism embodies and that she calls the Capitalocene. In other words, this is the reason why it is not the whole of ‘humankind’ being blamed for the particular geo-ecological crises of different times, but rather the specific socio-historical modes of extraction and repression that have always contributed to ecological regimes of the past and the present; examples include the plantation colonialism and contemporary agribusiness. In Haraway’s words, “cheap nature is at an end”, this reminds us that the commodification and commercial use of nature through capitalist methods is over and done with, resulting in the over exploitation of nature at a dismal state of existence for both men and animals.

However, Haraway does not let us remain in an abyss of despair. Rather, she proposes a more optimistic scenario through the notion of the Chthulucene which is a situation where there are intricate interconnections between different existences, humans and otherwise. This notion which advocates for “making kin” is one that goes against the ladder thinking or hierarchy which has civilized the western way of thinking for ages. Haraway proposes that ancestry politics is not sufficient and urges the creation of new kinships that cross social and ecological boundaries. For her, making kin is going beyond multiple pregnancies and childbirths to creating synergies with the other than human body. She remarks “making kin is perhaps the hardest and most urgent part" emphasizing that our future depends on forming these alliances across species boundaries.

DeleteThis idea of making kin presents deep similarities with what Hirshfield calls ecopoetics. Both propose that an anthropocentric worldview should be discarded in favor of the one that takes into account the intricacy of relationships in which the human beings with nature exist. For instance, in the retrospective accounts of poets such as Robinson Jeffers, she illustrates a need to elevate the horizons and consider the place of man as part of the ecosystem instead of being its tyrants. In the same vein, when Haraway presents the Chthulucene, she envisions a world where humanity is one of the many actors, and not the main actor, creating and sharing the planet with many other life forms. This change of attitude, from conquering an environment to interacting with it in a friendly manner, will contribute positively to the solutions of the contemporary environment-oriented problems.

What both Hirshfield and Haraway ultimately suggest is that the solutions to these crises are not only technical or scientific but also narrative and relational. The narratives we construct about the world, and those include poetry and philosophy as well as mundane conversation, in turn, influence our behavior as well as our moral principles. Therefore, remaining an external observer will always invite one to partake in the exploitation of nature; however, considering oneself a strand in a bigger, complex and dynamic network of existence will encourage most to adjust their ways to be environmentally friendly and ethical. As exemplified by Hirshfield’s ecopoetics, it is language that will help create these new forms of storytelling, while in Haraway’s case, kin-making stresses the importance of creating relationships that will enable us to survive the Chthulucene epoch.

Thus, both thinkers paint a picture that reconstructs the very meaning of humanity in new age era Anthropocene (or in the narrative of Capitalocene, Chthulucene). In light of the rapidly intensifying effects of climate change, the extinction of numerous species, and the depletion of resources, the ideas put forth by Hirshfield and Haraway are more pertinent than ever. They illustrate that the ecological issues we are experiencing are not merely a crisis of over-exploitation of resources and technological advancements but a more engrained crisis of the imagination and relations. In order to deal with this problem, we have to recontextualize how we view the world: not as conquerors, but as team players, not as simple solitary beings, but rather within a large web of life. It is in this that we can begin to salvage the wisdom and the humility that is required for coexistence with the earthly and all of its creatures.

Before deleving on what donna harawy article is about it must highlight the four important key words:

ReplyDeleteThe word Anthropocene comes from the Greek terms for human ('anthropo') and new ('cene'), is sometimes used to simply describe the time during which humans have had a substantial impact on our planet. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/what-is-the-anthropocene.html on other hand capitalocene a term that locates climate change within the history of capitalism and colonialism, and suggests stories that deserve time on our stages. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/the-drama-review/article/ . According to Donna Haraway, the Plantationocene is a way of conceptualizing the planetary impacts of the exploitation of natural resources, monoculture expansion, and forcible labor. Also, Chthulucene suggests an alternative story in which people are not the most important protagonists, the story is created by the practices of many creatures.

Donna Haraway, in Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin, delves into the detrimental effects of human activities on Earth's ecosystems and introduces different ideas to understand these changes. The Anthropocene denotes a time when human actions have drastically altered the planet, causing disruptions in ecosystems, pollution, and numerous extinctions. Haraway critiques this time as a period of harm that is irreversible. She explores further into the Capitalocene, arguing that the destructive tendencies of capitalism have caused extensive environmental harm through ongoing resource extraction. The Plantationocene connects environmental harm to colonial abuse, highlighting how the plantation system encourages extraction and control. Haraway's Chthulucene offers a favorable option. In this scenario, she envisions a future where collaborating with various species is crucial for thriving. Haraway encourages individuals to establish relationships with non-human species, imagining a future where humans live peacefully alongside other forms of life. Her idea of relations extends further than just immediate family or nearby neighbors and includes every being living on the planet. Her emphasis on a communal, multi-species strategy is vital to her ecological restoration vision, shifting away from a focus solely on humans. On the other hand, Jane Hirshfield talks about how poetry can address environmental crises in her Contemporary Practices Ecopoetics interview. Starting by tracing a lineage of literary works, starting from the « original sin » in the Epic of Gilgamesh, where the felling of a sacred tree symbolizes the human desire to dominate and separate from nature. According to Hirshfield, poetry is a powerful tool for observing the environment, allowing people to closely examine and reflect on the natural world. In her opinion, poetry can help create emotional connections not just among individuals but also with the whole natural world, such as ecosystems, plants, and animals, resulting in a greater sense of empathy. This feeling of empathy plays a key role in encouraging environmental awareness and, ultimately, action.

Hirshfield believes that art, especially poetry, serves as a connection between human consciousness and the natural world. While science explains ecological changes, poetry connects emotionally and imaginatively to the environment in a more personal and immediate way. Haraway and Hirshfield stress the interconnectedness of all life when addressing these subjects. Both suggest that humans have a strong connection to the environment. Nevertheless, Haraway stresses the significance of making changes by encouraging people to fundamentally change how they engage with non-human species and to embrace a future where humans and other life forms thrive together in peace. Hirshfield's main goal is to use poetry to increase awareness and encourage people to take action to protect the environment by strengthening their relationship with nature. While Haraway focuses on connections between different species, Hirshfield's method revolves around fostering empathy using artistic expression. Hirshfield believes that engaging in poetry through writing and reading can be a transformative experience that deepens one's appreciation of nature. Haraway focuses on extreme action, while Hirshfield underscores observation and emotional connection as essential aspects of ecological mindfulness. Both provide important viewpoints on reimagining the connection between humans and the environment. Haraway urges us to form ethical, symbiotic relationships with every species, moving beyond human dominance by "making kin." On the other hand, Hirshfield highlights how poetry can enhance our emotional bond with nature, encouraging us to be more accountable for its protection. While Haraway uses theoretical engagement and Hirshfield uses poetic compassion, both support changing our perception and interaction with the natural world.

Delete